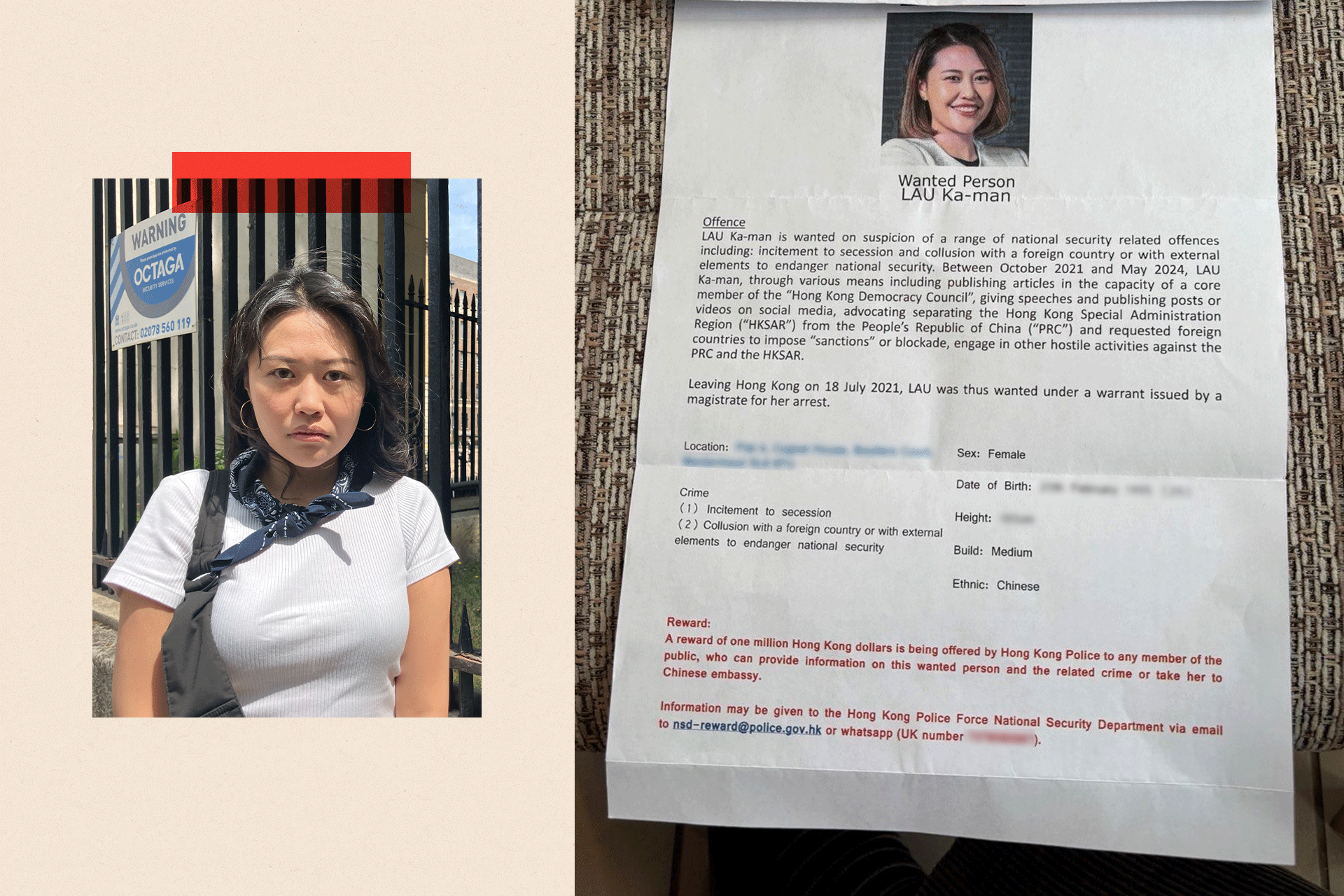

The sheet of paper says “Wanted Person” at the top. Below is a photo of a young woman, a headshot that might have been taken in a studio. She looks directly at the camera, smiling with her teeth showing, and her dark, shoulder-length hair is neatly brushed.

At the bottom, in red, are the words: “A reward of one million Hong Kong dollars,” together with a UK phone number.

To earn the money, about £95,000, there is a simple instruction: “Provide information on this wanted person and the related crime or take her to Chinese embassy”.

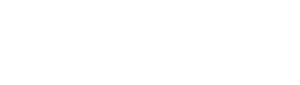

The woman from the photo is standing in front of me. She shudders when she looks at the building.

Hackers, secret cables and security fears: The explosive fight over the UK’s new Chinese embassy

We are outside an imposing structure that was once home to the Royal Mint and which China hopes it can develop into a new mega-embassy in London, replacing the far smaller premises it has occupied since 1877.

The new premises, opposite the Tower of London, is already being patrolled by Chinese security guards. The building is ringed with CCTV cameras too.

“I’ve never been this close,” admits Carmen Lau.

Carmen, who is 30, fled Hong Kong in 2021 as pro-democracy activists in the territory were being arrested.

She argues that the UK should not allow China’s “authoritarian regime” to have its new embassy in such a symbolic location. One of her fears is that China, with such a huge embassy, could harass political opponents and could even hold them in the building.

There are also worries, among some dissidents, that its location – very near London’s financial district – could be an espionage risk. Then there is the opposition from residents who say it would pose a security risk to them.

The plans had previously been rejected by the local council, but the decision now lies with the government – and senior ministers have signalled they are in favour if minor adjustments are made to the plan.

The site is sprawling, at 20,000 square metres, and if it goes ahead it would mark the biggest embassy in Europe. But would it also really bring the dangers that its opponents fear?

The biggest embassy in Europe

China bought the old Royal Mint Court for £255m in 2018. The area has layer upon layer of history: across the road is the Tower, parts of it were built by William the Conqueror. For centuries kings and queens lived there.

The plan itself involves a cultural centre and housing for 200 staff, but in the basement, behind security doors, there are also rooms with no identified use on the plans.

“It’s easy for me to imagine what would happen if I was taken to the Chinese embassy,” says Carmen.

In 2022, a Hong Kong pro-democracy protester was dragged into the grounds of the Chinese consulate in Manchester and beaten. British police nearby stepped over the boundary to rescue him.

Back in 2019, mass protests had erupted in Hong Kong, triggered by the government’s attempt to bring in a new law allowing for Hong Kong citizens to be extradited to China.

China’s response included a law that forced all elected officials in Hong Kong, including Carmen who was then a district councillor, to take an oath of loyalty to China. Carmen resigned instead.

She claims that journalists for Chinese state-run media started following her. The Ta Kung Pao newspaper, which is controlled by China’s central government in Beijing, ran a front page story alleging she and her colleagues had held parties in their council offices.

“You know the tactics of the regime,” she says. “They were following you, trying to harass you. My friends and my colleagues were being arrested.”

Carmen fled to London but believes that she has continued to be targeted.

Hong Kong issued two arrest warrants for her alleging “incitement to secession and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security”.

The bounty letter sent from Hong Kong to half a dozen of her neighbours followed.

“The regime just [tries] to eliminate any possible activists overseas,” she says.

Steve Tsang, a political scientist and historian who is director of the SOAS China Institute, says he can see why people from Hong Kong, or certain other backgrounds, may be uncomfortable with the new embassy.

He argues “the Chinese government since 1949 does not have a record of kidnapping people and holding them in their embassy compounds.”

But he says some embassy staff would be tasked with monitoring Chinese students and dissidents in the UK and they’d also target UK citizens, such as scientists, business people, and those with influence, to advance China’s interests.

The Chinese embassy told the BBC it “is committed to promoting understanding and the friendship between the Chinese and British peoples and the development of mutually beneficial cooperation between the two countries. Building the new embassy would help us better perform such responsibilities”.

Warnings about espionage

There is another fear, held by some opponents, that the Royal Mint Court site could allow China to infiltrate the UK’s financial system by tapping into fibre optic cables carrying sensitive data for firms in the City of London.

The site once housed Barclays Bank’s trading floor, so it was wired directly into the UK’s financial infrastructure. Nearby, a tunnel has, since 1985, carried fibre optic cables under the Thames serving hundreds of City firms.

And in the grounds of the Court, is a five-storey brick building – the Wapping Telephone Exchange that serves the City of London.

According to Prof Periklis Petropoulos, an optoelectronics researcher at Southampton University, direct access to a working telephone exchange could allow people to glean information.

Font: BBC News